2025.12.22

Others Plant science Story1991|Blue genes were isolated from petunias, and the patent of the gene was filed

There are many plants that produce blue flowers in nature, but our research team first chose a petunia exhibiting a dark violet color in order to isolate blue genes.

This article is a re-edited version of an article that appeared on our corporate website in 2014. Job titles, department names, and photos are current as of the time of publication (2014) and may differ from the present.

To develop a truly blue rose, the research team began by identifying the gene responsible for blue pigmentation, using dark violet petunias as a reference. To shorten the research cycle, they introduced candidate genes into yeast rather than plants, allowing them to test gene activity without waiting for flowers to bloom and dramatically accelerating the discovery process.

In 1991, the team succeeded in isolating the target gene for blue coloration and filed a patent application ahead of competing groups. This article looks back on the steady and determined research efforts that led to the successful identification of the gene.

Using yeast to dramatically accelerate research

This was because the petunia had already served as a model plant for the research of flower pigments (such as anthocyanin) and their biosynthesis and the following knowledge had already accumulated:

- Blue genes are cytochrome P450 type hydroxylase (enzymes involved in detoxification in the liver) genes.

- These genes work in petals but not in leaves.

- Red petunias that do not produce blue pigments do not have blue genes.

- Blue genes work most actively when petals are opening.

- Gene loci on the chromosomes were known.

We selected about 300 kinds of candidate genes from about 30,000 kinds of genes in petunias in order to identify the two blue genes of petunias. Our first plan was to introduce the candidate genes into petunias and observe flower color changes to determine whether they were actually blue genes. However, this method required several months until flowers bloomed to see color change. Therefore, to reduce the time required to obtain results, we decided to introduce the candidate genes of blue genes into yeast instead of plants and test their enzymatic activities in yeast. Thanks to this method, we obtained results in one week and were able to test the activities of many genes.

Successful isolation of the blue genes and filing of the patent

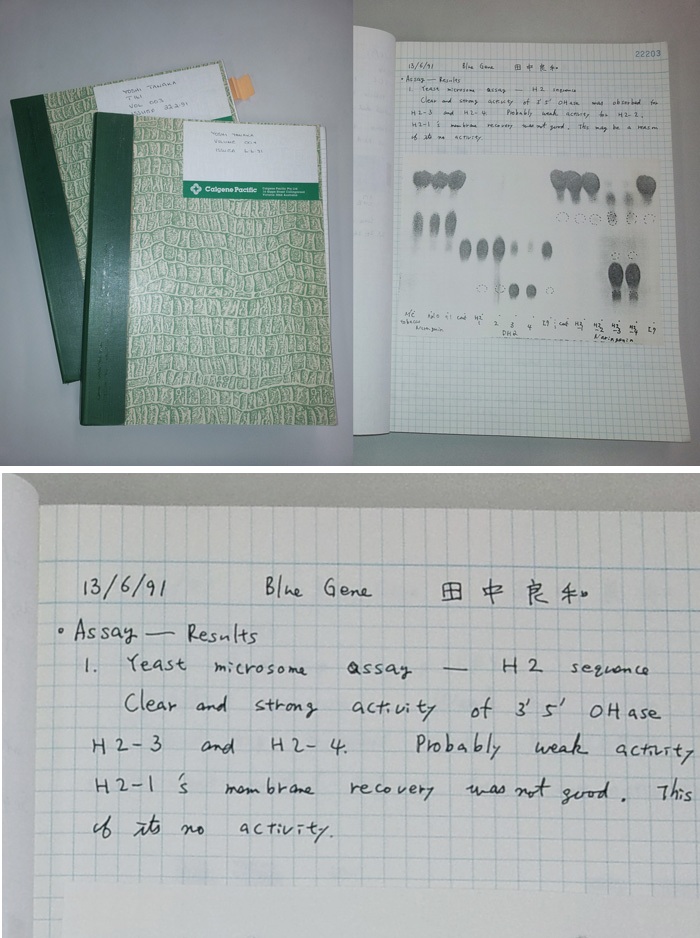

Finally, we succeeded in isolating blue genes on June 13, 1991.

Suntory and Florigene immediately applied for the patent of the blue genes. Because we applied for the patent earlier than any other competitors and monopolized the intellectual property right, we were able to engage in this research eliminating any competitors. We were also lucky to be granted with broad claims because our applications were the first ones for patents of genes with this kind of activity. Actually, introduction of these genes into petunias and tobacco resulted in the increase of blue pigments “delphinidin.” Our paper describing these results was published in “Nature,” the most prestigious scientific journal in the world.

The time when we discovered blue genes was the happiest moment of my research life (Senior General Manager Yoshikazu Tanaka Ph.D.)

Circle mark on a fax sent to Japan, conveying good news

The work to isolate blue genes, which would be the key to producing blue roses, needed patience. We introduced isolated genes into yeast, grew them, and examined whether a precursor of blue pigments had been produced by exposing them to X-ray films—I patiently repeated this steady process.

On one day, a spot indicating the blue gene activities which I had not seen before appeared on an X-ray film. Finally we succeeded in isolating blue genes.

I cannot fully express the sensation that I felt at the time. Immediately, I sent a fax with a big circle mark to Japan. Although no word was written on it, colleagues in Japan knew what it meant, and shouted with pleasure, “They did it!”

When I said “I think I got one” to a colleague at Florigene, the news spread in an instant and they also got excited. A female director in charge was also pleased, with red eyes and tears. The president of Florigene bought us lunch on that day. We had a party celebrating the success at an Italian restaurant.

While everyone was pleased and excited, my colleagues from Japan and I were thinking about the possible difficulties in introducing the blue genes into roses and carnations. Even though we had isolated blue genes, all the efforts would be in vain without producing blue flowers.

It was fortunate that use of yeast accelerated the identification of the genes

In July, we applied for the patent of blue genes. We found later that a competing research team also succeeded in isolating genes about the same time. Fortunately, however, we made the application earlier than them, and obtained patents without any trouble.

In the experiments to narrow down candidate genes, we used yeast to reduce the time to produce results, which was perhaps very fortunate for us. If we had used plants, not yeast, for the experiments, we might have made the application later and might have failed to obtain the patent right.

To express plant genes in yeast, we applied the yeast expression system that had been developed by medical research Suntory engaged at that time. As in this case, techniques that were developed in the past can sometimes be used for a totally different research later.

We introduced candidate genes into petunias, but the color of petals did not change, and we were disappointed for a moment. However, we took a closer look and found that the color of pollens only had turned blue. We screamed, “Thank God!” and laughed. It is such a nice memory. Subsequently, we confirmed that the color of petals could be turned blue, too. This was the moment when I was convinced that blue flowers of roses and carnations could be produced eventually.