Satoyama Forest Management

Preventing Evergreening of Deciduous Broadleaved Forests

For centuries, Japan’s satoyama woodlands—woodlands in mountain foothills adjacent to settlements in rural valleys—have been preserved as bright, lively spaces. They have served as sources of firewood, charcoal, humus and cuttings for fertilizer, mushrooms, edible wild plants and more.

Of course, from that time, evergreens such as East Asian euryas, Japanese blue oaks and camphor trees would sprout in these forests from seeds brought by birds and other methods, but these were typically cut for firewood or kindling when they were still small and therefore never grew to become the dominant trees in the forests. This style of forest management has long allowed satoyama woodlands to remain filled with natural sunlight and maintain healthy ecosystems hosting unique plant life.

However, as populations left the mountains and these woodlands were abandoned and left unmanaged, the unharvested evergreens grew unchecked, eventually blocking out light from the forest floor. Ecosystems that were maintained for centuries began to vanish due to lack of light, creating a biodiversity crisis.

Removing all evergreens, both large and small, that have infiltrated deciduous broadleaf forests allows sunlight to again reach the forest floor. This allows the trees and grasses unique to sunlit forests to start to recover, and biodiversity is restored. The colors of the seasons are regained.

Suntory Group employees experience forest maintenance in our Natural Water Sanctuaries as part of their training. During this activity, they also remove evergreen trees.

Experts involved in this Initiative

Tamotsu Hattori

Emeritus Professor, University of Hyogo

Institute of Rural and Urban Ecology Co., Ltd.

Regional Environmental Planning, Inc.

Learn about our activities related to implementation

Research Conducted with Experts

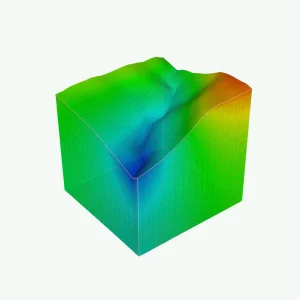

By combining field investigations with simulations, we ascertain the current health of the forest and forecast its future.

Planning Based on Forest Surveys

Vision Development

In our Natural Water Sanctuaries, conservation and restoration efforts are taken with a long-term perspective spanning 30 to 100 years. The foundation of this effort is the development of a vision.

Since forest conditions vary significantly from one location to another, thorough surveys are conducted to examine both past developments and the current situations. The surveys involve a wide range of tools and information, including topographic maps, aerial photographs, existing vegetation classifications, and the characteristics of individual plant communities*.

Based on the survey results, discussions are held with vegetation consultants, forestry experts, and other specialists to identify issues for each plant community. Subsequently, multiple solutions are proposed for each identified issue, and maintenance policies are determined accordingly. By updating each vision every 5 to 10 years, the Sanctuaries undergo continuous evaluation and improvement.

A community is a group of plants that inhabit the same location.

Experts involved in this Initiative

Regional Environmental Planning, Inc.

Institute of Rural and Urban Ecology Co., Ltd.

MORISHO LLC

AI-Shokubutsu Landscape Planning Office

Implementation of Forest Management Plans

We carry out restoration and maintenance activities in collaboration with professionals from various fields.

Improvement Through Ongoing Surveys

The plants and animals living in forests are constantly changing. In our Natural Water Sanctuaries, ongoing surveys are conducted to inform continuous improvements.

Examples of Our Activities

When working with nature, things don't always go as planned. That's why ongoing surveys after forest maintenance are crucial. Sometimes, results exceed expectations, while other times, efforts end in complete failure. Here are some examples of challenges and discoveries encountered during our activities.

These Deer Weren't Here Last Year

In our Natural Water Sanctuary Okudaisen, 2 to 3 meters of snow accumulates during winter. Because of this, deer had never been seen in the area until recently. However, signs of deer feeding on grass and shrubs started to appear. In response, cameras were immediately set up, revealing a significant presence of deer.

The original maintenance plan for our Natural Water Sanctuary Okudaisen was designed for a forest without deer. Until recently, this sanctuary stood out as an exceptional example where biodiversity thrived and maintenance results were highly effective.

Unfortunately, the unexpected arrival of deer meant the plan had to be completely revised. The first step was to fence off key areas. However, standard metal fences would be damaged as melting snowpacks move during the spring thaw. To address this, we are taking an emergency measure of installing a resin net immediately after the snow begins to melt, and then laying the net flat on the ground when the snow starts to accumulate.

A Mountain Made of Pumice?

When the agreement was signed to create our Natural Water Sanctuary Shizuoka Oyama, the most surprising aspect of the forest management challenge was the fragility of the mountainside. The majority of the existing logging roads had been severely eroded by heavy rains, leaving deep trenches throughout.

In fact, this mountain is composed of alternating layers of volcanic ash from past eruptions of Mount Fuji and small pumice stones called scoria. When roads or other clear-cuts expose the ground, the pumice layer is quickly eroded by water.

As a result, we decided to turn unnecessary logging roads back into forest. Unfortunately, these areas are also frequented by many deer. So, on the flat roadbeds we planted mitsumata (Oriental paperbush) and susuki (Japanese silver grass), which are less palatable to deer. Although susuki is generally disliked by deer, for some reason they like to pull out the young plants. So, we are covering them with agricultural bird netting until they are well-established. The broadleaf trees planted on one side are being protected as individual trees.

New Discoveries During Forest Management

As we continue to repeat our process of R-PDCA (research, plan, do, check, and act), we sometimes make unexpected discoveries. Here are some of the surprising discoveries we have made about wildlife during our forest management activities.

Deer Feeding Almost Exclusively on Fallen Leaves During Winter!

As part of our Natural Water Sanctuary Project Chichibu with the Univ. of Tokyo, we conducted DNA analysis of deer droppings to investigate what they eat in different seasons. The results were astonishing.

During winter, the primary food source for deer turned out to be maples and dogwoods. However, both of these tree types are deciduous. This means in winter, there are no green leaves available to eat. Later, using footage from fixed-point cameras we confirmed that deer herds are feeding on fallen leaves. As you can see, the deer were in good condition and showed no signs of malnutrition.

If deer can survive on fallen leaves, then their food resources are virtually limitless. This discovery invalidates the once-optimistic assumption that if deer eat up all the undergrowth, they will eventually starve and their numbers will decline. We are now developing new strategies to protect forest biodiversity.

Experts involved in this Initiative

Hirao Toshihide

Lecturer, The University of Tokyo

A Possible Solution for Invasive Bamboo?

In our Natural Water Sanctuary Tennozan, a logging road was built alongside a bamboo grove. To protect the road’s embankments (norimen*1), we planted mitsumata (Oriental paperbush) —a species that deer do not eat.

Then, something unexpected happened. Along the sides of the road where mitsumata was densely planted, bamboo shoots stopped sprouting. It appears that mitsumata has an allelopathic effect*2 that inhibits bamboo roots. If this proves correct, it could be a breakthrough solution for controlling invasive bamboo across Japan.

- Norimen refers to the slopes created on both sides of a logging road.

- Allelopathy is the phenomenon where chemicals released by one plant influence the growth of other plants or microorganisms.

Home

Home Initiative Policy and Structure

Initiative Policy and Structure Living Things in the Natural Water Sanctuaries

Living Things in the Natural Water Sanctuaries Dedication to Water

Dedication to Water Natural Water Sanctuaries

Natural Water Sanctuaries  Natural Water

Natural Water  Initiative History

Initiative History