Vegetation and Bird Surveys

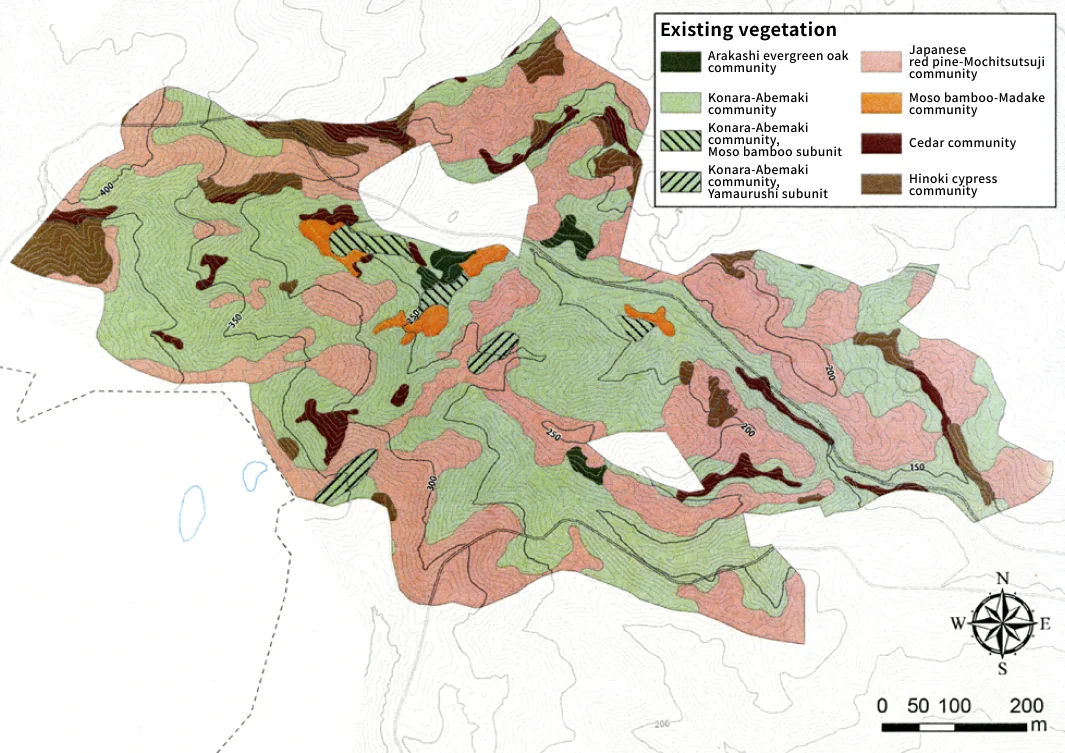

Vegetation Survey

No two Natural Water Sanctuaries across Japan are alike. Even within a single forest, the types and conditions of plants growing in an area varies significantly due to the complex interplay of multiple environmental factors.

To properly manage each forest, it is essential to divide areas based on vegetation patterns and forest types and develop a management plan through a process called forest zoning.

To conduct proper zoning, the essential step is a detailed vegetation survey to understand the forest's current condition.

The vegetation survey process begins with an aerial photograph analysis to gain a preliminary understanding of the plant distribution. Next, field surveys are conducted, where 10-meter by 10-meter plots are set within each plant community*, and all plant species within these plots are identified and recorded.

A community is a group of plants that inhabit the same location.

Based on the survey data, a vegetation map is created, providing a visual representation of the plant species living in the forest. This vegetation map serves as a key resource for developing long-term forest management plans for the next 50 to 100 years.

Experts involved in this Initiative

Tamotsu Hattori

Emeritus Professor, University of Hyogo

Yoshiyuki Hioki

Specially Appointed Professor, Tottori University

Regional Environmental Planning, Inc.

Institute of Rural and Urban Ecology Co., Ltd.

MORISHO LLC

AI-Shokubutsu Landscape Planning Office

Bird Surveys

Wild birds serve as an important indicator of forest health. In our Natural Water Sanctuaries, bird surveys are conducted with the cooperation of experts to monitor the state of the forest and maintain an environment where birds can thrive. The surveys primarily involve fixed-point surveys, route censuses, and discretionary exploratory surveys.

For fixed-point surveys, a vantage point with a clear view of the forest area is selected for each Natural Water Sanctuary, and observers remain there for an extended period to record all bird species that appear. Particular attention is given to raptors, which sit at the top of the forest ecosystem. Observers document their flight paths and behaviors as crucial data points.

With the route census method, a 1–2 km survey route is established within each Natural Water Sanctuary in walkable areas that provide a representative view of the forest environment. Surveyors walk slowly along the route, recording bird species and individual counts. The goal is to gain an overall understanding of the bird population within the forest and track changes over time.

The discretionary exploratory survey supplements the fixed-point survey and route census by gathering additional seasonal and site-specific data that may not be obtained otherwise. It is particularly important for identifying potential nesting sites of raptors to ensure that forestry operations do not disturb their habitats.

If nesting sites or frequently used feeding grounds of raptors are discovered during a survey, their breeding and habitat conditions are then closely monitored to minimize any impact from forest operations and enhance their living environment.

Additionally, Ural Owl nest boxes are installed in our Natural Water Sanctuaries to support Ural Owl breeding. Ural Owls require large tree cavities for raising their young, but such nesting sites have become increasingly scarce, leading to a housing shortage. The nest boxes provide temporary homes until the forests mature enough to naturally develop tree hollows. Researchers also analyze food traces left inside the nest boxes to study what the Ural Owls eat and feed their chicks. These findings help assess the forest's ecological health.

Bird names are listed in accordance with the Check-list of Japanese Birds, 8th Revised Edition.

Suntory conducts regular bird surveys from multiple angles. These surveys help reveal which bird species inhabit the forest and how they live. We also monitor whether raptors, which sit at the top of the ecosystem, can sustain their populations. This is a key indicator for creating forests that benefit both birds and humans.

Experts involved in this Initiative

Takashi Fujii

Research Manager, Japanese Society for Preservation of Birds Research Department

MORISHO LLC

Jun Nonaka

Representative, The Japan Accipiter Working Group

Learn about the attention to detail in tree planting

Research Conducted with Experts

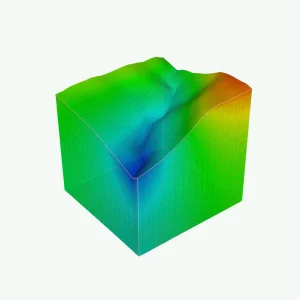

By combining field investigations with simulations, we ascertain the current health of the forest and forecast its future.

Planning Based on Forest Surveys

Vision Development

In our Natural Water Sanctuaries, conservation and restoration efforts are taken with a long-term perspective spanning 30 to 100 years. The foundation of this effort is the development of a vision.

Since forest conditions vary significantly from one location to another, thorough surveys are conducted to examine both past developments and the current situations. The surveys involve a wide range of tools and information, including topographic maps, aerial photographs, existing vegetation classifications, and the characteristics of individual plant communities*.

Based on the survey results, discussions are held with vegetation consultants, forestry experts, and other specialists to identify issues for each plant community. Subsequently, multiple solutions are proposed for each identified issue, and maintenance policies are determined accordingly. By updating each vision every 5 to 10 years, the Sanctuaries undergo continuous evaluation and improvement.

A community is a group of plants that inhabit the same location.

Experts involved in this Initiative

Regional Environmental Planning, Inc.

Institute of Rural and Urban Ecology Co., Ltd.

MORISHO LLC

AI-Shokubutsu Landscape Planning Office

Implementation of Forest Management Plans

We carry out restoration and maintenance activities in collaboration with professionals from various fields.

Improvement Through Ongoing Surveys

The plants and animals living in forests are constantly changing. In our Natural Water Sanctuaries, ongoing surveys are conducted to inform continuous improvements.

Examples of Our Activities

When working with nature, things don't always go as planned. That's why ongoing surveys after forest maintenance are crucial. Sometimes, results exceed expectations, while other times, efforts end in complete failure. Here are some examples of challenges and discoveries encountered during our activities.

These Deer Weren't Here Last Year

In our Natural Water Sanctuary Okudaisen, 2 to 3 meters of snow accumulates during winter. Because of this, deer had never been seen in the area until recently. However, signs of deer feeding on grass and shrubs started to appear. In response, cameras were immediately set up, revealing a significant presence of deer.

The original maintenance plan for our Natural Water Sanctuary Okudaisen was designed for a forest without deer. Until recently, this sanctuary stood out as an exceptional example where biodiversity thrived and maintenance results were highly effective.

Unfortunately, the unexpected arrival of deer meant the plan had to be completely revised. The first step was to fence off key areas. However, standard metal fences would be damaged as melting snowpacks move during the spring thaw. To address this, we are taking an emergency measure of installing a resin net immediately after the snow begins to melt, and then laying the net flat on the ground when the snow starts to accumulate.

A Mountain Made of Pumice?

When the agreement was signed to create our Natural Water Sanctuary Shizuoka Oyama, the most surprising aspect of the forest management challenge was the fragility of the mountainside. The majority of the existing logging roads had been severely eroded by heavy rains, leaving deep trenches throughout.

In fact, this mountain is composed of alternating layers of volcanic ash from past eruptions of Mount Fuji and small pumice stones called scoria. When roads or other clear-cuts expose the ground, the pumice layer is quickly eroded by water.

As a result, we decided to turn unnecessary logging roads back into forest. Unfortunately, these areas are also frequented by many deer. So, on the flat roadbeds we planted mitsumata (Oriental paperbush) and susuki (Japanese silver grass), which are less palatable to deer. Although susuki is generally disliked by deer, for some reason they like to pull out the young plants. So, we are covering them with agricultural bird netting until they are well-established. The broadleaf trees planted on one side are being protected as individual trees.

New Discoveries During Forest Management

As we continue to repeat our process of R-PDCA (research, plan, do, check, and act), we sometimes make unexpected discoveries. Here are some of the surprising discoveries we have made about wildlife during our forest management activities.

Deer Feeding Almost Exclusively on Fallen Leaves During Winter!

As part of our Natural Water Sanctuary Project Chichibu with the Univ. of Tokyo, we conducted DNA analysis of deer droppings to investigate what they eat in different seasons. The results were astonishing.

During winter, the primary food source for deer turned out to be maples and dogwoods. However, both of these tree types are deciduous. This means in winter, there are no green leaves available to eat. Later, using footage from fixed-point cameras we confirmed that deer herds are feeding on fallen leaves. As you can see, the deer were in good condition and showed no signs of malnutrition.

If deer can survive on fallen leaves, then their food resources are virtually limitless. This discovery invalidates the once-optimistic assumption that if deer eat up all the undergrowth, they will eventually starve and their numbers will decline. We are now developing new strategies to protect forest biodiversity.

Experts involved in this Initiative

Hirao Toshihide

Lecturer, The University of Tokyo

A Possible Solution for Invasive Bamboo?

In our Natural Water Sanctuary Tennozan, a logging road was built alongside a bamboo grove. To protect the road’s embankments (norimen*1), we planted mitsumata (Oriental paperbush) —a species that deer do not eat.

Then, something unexpected happened. Along the sides of the road where mitsumata was densely planted, bamboo shoots stopped sprouting. It appears that mitsumata has an allelopathic effect*2 that inhibits bamboo roots. If this proves correct, it could be a breakthrough solution for controlling invasive bamboo across Japan.

- Norimen refers to the slopes created on both sides of a logging road.

- Allelopathy is the phenomenon where chemicals released by one plant influence the growth of other plants or microorganisms.

Home

Home Initiative Policy and Structure

Initiative Policy and Structure Living Things in the Natural Water Sanctuaries

Living Things in the Natural Water Sanctuaries Dedication to Water

Dedication to Water Natural Water Sanctuaries

Natural Water Sanctuaries  Natural Water

Natural Water  Initiative History

Initiative History