Suntory Hall Summer Festival 2025

Theme Composer Georges Aperghis

A Dialogue with the World

Exploring the Work of Georges Aperghis

The theme composer for the Suntory Hall Summer Festival 2025 (August 23–30) is Greek-French composer Georges Aperghis. His works are not bound by any dominant aesthetic of contemporary music; instead, they evolve through dialogue with other art forms and are rooted in 20th century traditions. The three concerts at the festival will showcase the wide-ranging appeal of his music, featuring Japanese premieres of orchestral and chamber works for various ensembles, as well as his signature solo vocal piece Récitations.

Musicologist Nicolas Donin offers some insights into Aperghis's creative world.

The music of Georges Aperghis is a dialogue with the world. It blends together the sounds of instruments and those of language. It takes inspiration in the work of filmmakers, painters, philosophers as well as anthropologists. It collides the diversity of languages. It is not afraid to connect stage actions with video, gestures, and electronic sounds. Over the last sixty years, Aperghis has tirelessly experimented with virtually every musical and stage genre. His catalogue now includes eight operas, seventeen musical theatre pieces, some forty works for vocal, instrumental and orchestral ensembles, thirty solo pieces, and forty chamber music works for 2 to 10 performers. At times, his art has also taken other forms: graphic works, poetic texts to perform, or collective improvisation workshops. In the midst of this abundant diversity, however, we find recurring threads, and above all a highly personal style—a musical discourse that is fast, dense, nervous, sometimes choppy, and which readily plays on effects of contrast, surprises, and sudden reversals of situation.

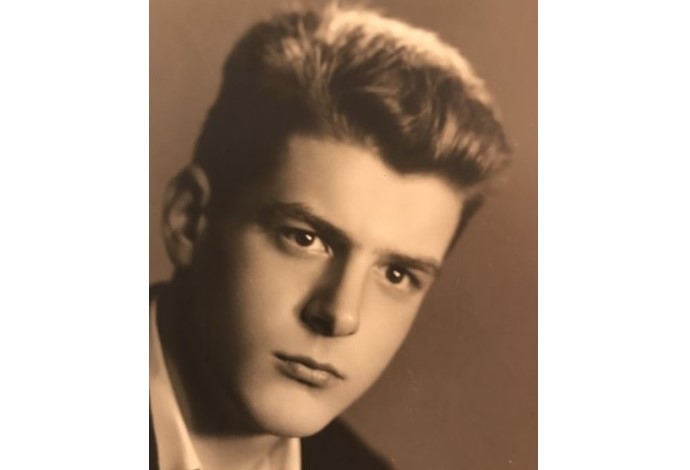

From Athens to Paris, from painting to music

Born in Athens in 1945 into a family of artists, Aperghis initially developed a passion for visual arts. He spent part of his youth in his own studio practising a gestural style of painting inspired by North American and European abstraction. His oil paintings were the subject of two monographic exhibitions in an Athens art gallery, Nées Morphès (‘New Forms’), when the artist was still in his teens. At the same time, he was developing his interest in music and theatre.

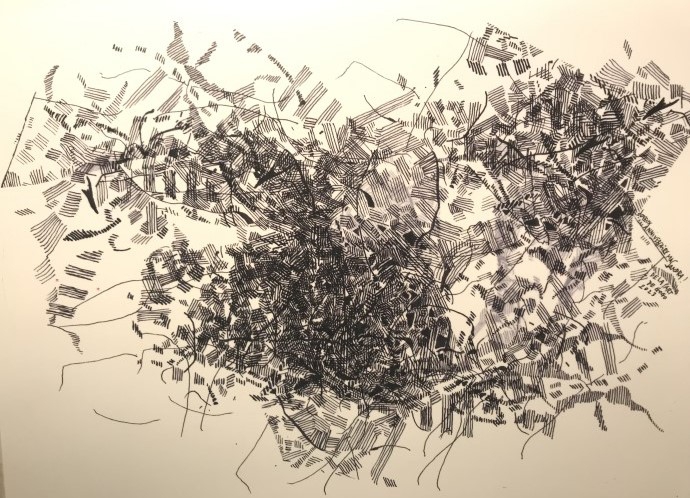

But it was when he arrived in Paris at the age of seventeen that he decided to devote himself to music. He discovered the world of Cage and the Fluxus group, became familiar with the music of Xenakis and then Kagel, composed his first works and took part in an avant-garde collective called Méta-Art. Throughout the 1960s, he learned (largely self-taught) his craft as a composer and, at the same time, challenged it through graphic scores that evaded the conventions of solfeggio.

Aperghis followed a personal path amid the cultural, social and aesthetic upheavals of the late 1960s, marked by major political events such as the French youth revolt of May 1968. For him, modern art in all its forms was primarily a lesson in freedom, experimentation and invention, rather than a critique of society. Was there a way to create musical propositions as beautiful and surprising as, say, a film by Michelangelo Antonioni, a novel by Virginia Woolf or a ‘combine’ by Robert Rauschenberg?

Music and/on stage

His meeting in 1964 with the actress Édith Scob (1937-2019) inaugurated both a love and an artistic partnership spanning several decades. Scob introduced Aperghis to the playwright Arthur Adamov, the filmmaker Georges Franju, the director Antoine Vitez (with whom Aperghis in turn collaborated on several projects over the 1970s and 1980s), as well and many other leading figures in French intellectual and artistic life.

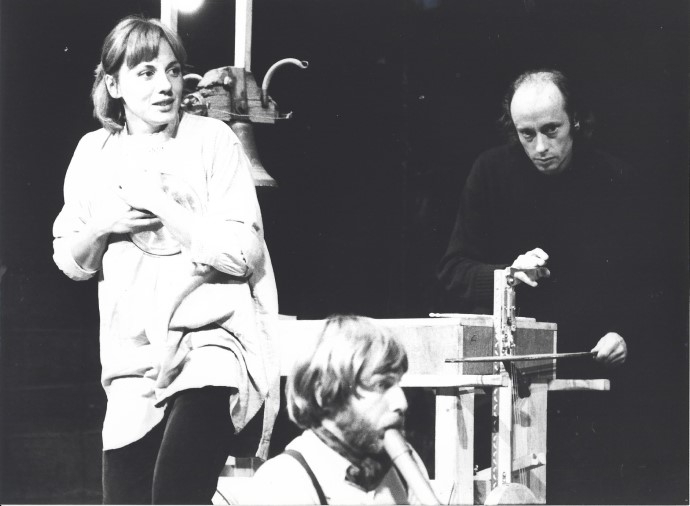

Alongside her career in film and theatre, Édith Scob was a member of a small group of performers who worked with Aperghis to develop techniques for improvising with sound, words and gestures, as part of the ‘Atelier Théâtre et Musique’ (ATEM), established in 1976 in Bagnolet, a poor suburb of Paris. This improvisation work was meant to lead to original shows with a social dimension: local residents could attend and take part, helping to define the themes of the shows. This way of working enabled Aperghis to expand on the stage work he had already begun in 1971 with La Tragique Histoire du nécromancien Hiéronimo et de son miroir (The Tragic Story of the Necromancer Hieronimo and his Mirror) , a theatrical and musical production that was his first big success at the Avignon Theatre and Dance Festival. Over the years, thanks to weekly workshops in improvisation on the border between music and theater, the small community of performers of 1976 grew up and became a kind of experimental troupe, famed for its interdisciplinary virtuosity.

Their domain is now well-known as ‘musical theatre’. What does it mean? This word, often used in relation to Aperghis, Mauricio Kagel, Dieter Schnebel and many other creators after them, refers to a stage performance in which sounds, words and actions are organised according to a musical structure (through imitations, transformations, or polyphony) rather than a narrative or dramaturgical structure as one would find in theatre or opera. In his musical theatre works, Aperghis creates ‘situations’ that cannot be summed up by verbal logic, which the actor-instrumentalists explore in unexpected and often playful ways—Aperghis's music is one of the very few in contemporary music to elicit laughter, to dare to be humorous. From a strictly musical point of view, this means that Aperghis does not limit the field of composition to the writing of a score, nor does he limit the field of interpretation to the production of the sounds prescribed by that score. Rather, he builds up a ‘musical body’, to quote the title of a book devoted to his work by Antoine Gindt (Arles, Actes Sud, 1990).

(ATEM, Festival d'Avignon, 1977)

Playing with pebbles

Since the early 1970s, there have been two Aperghis, as it were. One is a solitary composer writing chamber or orchestral scores for musicians and groups of musicians with whom he enjoys developing a close and friendly working relationship—for example Klangforum Wien (Vienna), MusikFabrik (Cologne), the Neue Vocalsolisten (Stuttgart), Ictus (Brussels) or Remix (Porto), to name but a few in the last quarter of a century. The other Aperghis is the leader and director of a musical theatre troupe—first the members of ATEM mentioned above, then, after 1997, groups formed specifically for each new show.

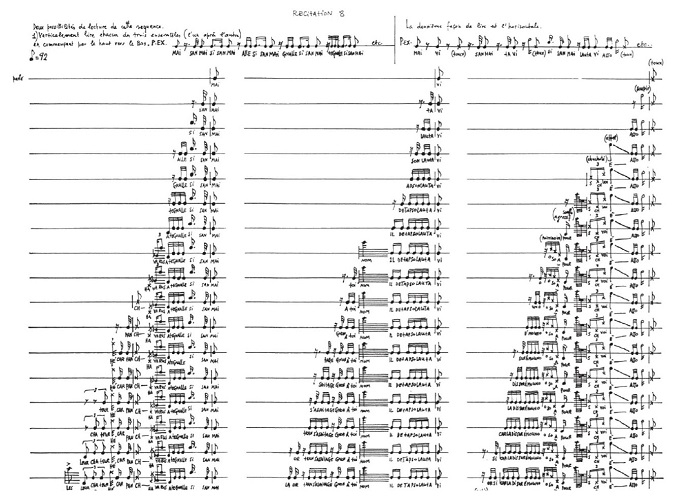

But some works seem to straddle the line between these two facets of the composer. This is the case with Récitations, for solo voice (1978), a collection of 14 short pieces (usually lasting from 1' to 4' each) that can be played in an order chosen by the performer. Each piece explores a particular relationship between notes, syllables and qualities of vocal timbre. Often, the appearance of the score gives a clear indication of the musical form: for example, Récitation 1 is made up of variations based on a small group of notes, sometimes enriched, sometimes pulverised. Or Récitations nos. 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 work by accumulation: the singer pronounces a sound (phoneme or syllable) at a given pitch, then that same sound preceded or followed by another, then those two sounds preceded or followed by another, and so on. Almost algorithmic, this mechanism seems easy to understand at first, but after a few rounds, perception is completely overwhelmed by the flood of musical information, reinforced by the lack of immediate meaning of the sung ‘text’. Each Récitation then appears like a mini-scene of musical theatre in which the soloist follows a different course of action, thus embodying a different musical character. But this ‘character’ could not be described by a theatrical didascalia. It is neither a lyrical heroine nor a melancholic narrator, but a chimera of sound, created entirely by the logic of unpredictable musical combinations.

Donatienne Michel-Dansac (Voice)

Christian Dierstein, Dirk Rothbrust (Percussion)

Marco Blaauw (Trumpet)

Sophie Lücke (Double bass)

© Heinrich Brinkmöller-Becker, Ruhrtriennale 2023

In several Récitations pieces, a list of notes (e.g. low C, high F sharp, E in mid-register, etc.) is associated in a fixed way with a list of verbal atoms (e.g. the phoneme ‘u’, the syllable ‘ki’, etc.) and with a list of sound colours (e.g. a sound reminiscent of a gong, of a flute, etc.). Each time you hear a given note, it comes with the same ‘text’ and ‘timbre’. Aperghis plays with these elements in the same way as a child might play with pebbles, small stones, or bits of wood: he invents an alphabet, tries out different ways of ordering these sound objects, sketches out imaginary stories—or rather, he offers us ways of making our own imaginary stories out of the assemblages fixed in the score.

Récitations on Apple Music

Playing with large forms

Arranging discrete elements in an unexpected order as means to generating attention and interest for the listener, is of course not a characteristic of the composition of Récitations only. This approach can be found in most of Aperghis's works, including those with large temporal dimensions (for example, in a symphonic work or a stand-alone musical theater piece). Aperghis likes to work with highly contrasting basic materials and to devise a musical form that allows them to cohabit without losing their identity or their own energy. Sometimes the heterogeneity is a source of surprise that feeds the listener's curiosity, and sometimes the heterogeneity is too strong and disperses the listener's attention. Each work therefore requires a specific method of writing that cannot be reproduced for another work using another material. The Études pour orchestre (Studies for orchestra) are a privileged locus for this kind of formal reflection. Faced with the great human and sonic machine that is the symphony orchestra, faced with the innumerable layers of musical history that make up its sound, Aperghis did not want to position himself either as a modern (by inventing a brand new language) or as a postmodern (by playing with the past through borrowing and irony). He simply sought to use his writing techniques as a means of empirical exploration. As the composer told me in the conversation book we published together in 2022: ‘Each study is an answer to the question: "How can I create a particular surface with the orchestra?" and an attempt to realise my ideal of a music without beginning or end’. Thus, throughout the works in this series (Études I-IV [2012-14], V-VI [2014-15], VII [2022] and now VIII [2025], all premiered under the baton of Emilio Pomàrico), one encounters very different instrumental combinations from one piece to the next, unstable orchestral textures, and formats ranging from less than 2 minutes (Étude VI) to around 20' (Étude VIII)!

Emilio Pomàrico (Conductor)

Teodoro Anzellotti (Accordion)

Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks (BRSO)

(the Herkulessaal in Munich, 2016)

Idiomatic music

Aperghis's work, heir to the musical avant-gardes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, is characterised by a questioning of language and meaning. His compositions, whether instrumental, vocal or theatrical, explore the boundaries between music and speech. They challenge our perception of the fundamental elements of human communication, such as the phoneme, gesture, or phrasing. Although they often feature monologues, ruminations, individuals isolated in their idiom, they always end up creating large spaces for dialogue, because their expressiveness is not tied to a prior theory, or a message to be delivered. Rather, they deconstruct the expectations formed by the institutions of concert and opera. In so doing, they suggest to listeners that the world might be different from what it is; that in life, as in the forms of his compositions, nothing ever goes according to plan; that our freedom is exercised not only in our very conscious decisions but in the perceptual act itself, beyond any control; and that the audience always participates in the works, even without knowing it.

Nicolas Donin ©2025

Nicolas Donin is Professor and Chair in musicology at the University of Geneva. He specialises in the history, aesthetics, and creative process of 20th and 21st century musics. He recently published a conversation book with Georges Aperghis (Conversation imagée, Paris, Editions de la Philharmonie, 2022).

- Video: Interview with Georges Aperghis about his Études V & VI