- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

"Mono no Aware" and Japanese Beauty

April 17 to June 16 2013

Part 1

The origins of mono no aware:

Aristocratic lifestyles and courtly elegance

The phrase mono no aware, which refers to the sensitive, exquisite feelings experienced when encountering the subtle workings of human life or the changing seasons, has been used since the Heian period. While aspects of mono no aware have long been part of the human experience, the concept and the sensibilities associated with it were refined during the Heian and Kamakura periods as part of the lifestyles of aristocrats associated with the imperial court.

Here, by examining in detail picture scrolls dating back to those periods, including the Tale of Nezame, The Retired Emperor Visits Ono to View the Snowy Scenery, and the Tale of Toyo no Akari, we attempt to trace the foundations and origins of the sentiments found in mono no aware. These picture scrolls depict the lives of courtly refinement enjoyed by aristocrats through the process known as tsukuri-e, which was admirably suited to providing a visual representation of the deeply felt lyrical qualities of the narratives. With the tsukuri-e use of bright, opaque color and delicate brushwork to present the spaces within fukinuki yatai, “roofless buildings,” and the human characters with their hikime kagibana, “slit eyes and hooked noses,” these scroll paintings are rich in emotional implications. Color is not, however, essential: in hakubyo-e, monochrome paintings created with fine, taut brushwork, the lack of color combined with exquisite restraint suffuses the picture plane with the aura of mono no aware.

National Treasure

The Tale of Nezame Picture Scroll

Handscroll, color on paper

Heian period (12th century)

The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

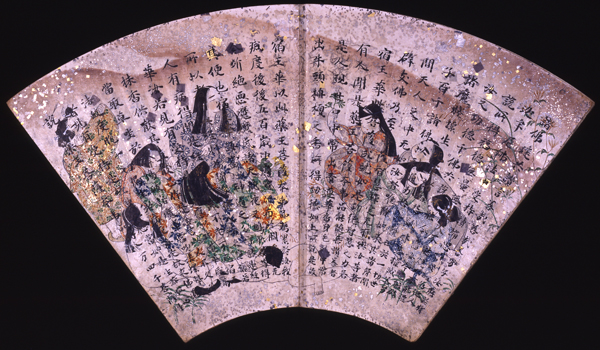

National Treasure

Lotus Sutra on Fan Paper

(originally in bound book form)

One sheet, color on paper

Heian period (12th century)

Shitenno-ji temple

Part 2

The phrase mono no aware and Motoori Norinaga

The connotations of the phrase mono no aware diverge over interpretations of aware. Use of the Chinese character for “sad” to render the Japanese word aware associates mono no aware with sad or fleeting experiences. That nuance is not, however, intrinsic to the phrase, whose essence is the experience of being deeply moved by emotions that may include joy and love as well sadness.

It is Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801) to whom we owe our understanding of mono no aware. In his writings examining the concept, Norinaga noted that experiencing mono no aware means savoring life more deeply. In this exhibition, we will consider emotions we all experience, that well up in response to the joy, anger, pathos, and humor of human life and in response to the passage of the seasons, as exemplified by the classic “sun, moon, flower” theme in paintings. The works of art displayed here are suffused with the feelings of their creators, whose individual styles and techniques communicate mono no aware nonverbally in a variety of forms.

An Annotated Version of the Tale of Genji (Shibun Yoryo), Bound Author’s Manuscript

Motoori Norinaga

Two volumes, ink on paper

Edo period; Horeki 13 (1763)

Museum of Motoori Norinaga

Part 3

Mono no aware in the literary classics:

The Tale of Genji

The Tale of Genji depicts Heian-period aristocrats’ love of nature throughout the seasons and describes their emotions in interacting with others. This refined, lyrical tale has long been a favorite subject for picture scrolls, folding screens, and craft objects. It also continues, to this day, to occupy a special position in classical literature.

Motoori Norinaga argued that Murasaki Shikibu wrote the Tale of Genji to make people more profoundly aware of mono no aware. The “Sakaki” (sacred tree) chapter shows Genji and his attendants on their way to visit Lady Rokujo in Nonomiya. In the “Suma” chapter, Genji is gazing at the moon. In “Ukifune” (boat on the water), from the ten Uji chapters, the prince Nyo no Miya and Ukifune are shown together in a boat in the moonlight. All these scenes evoke mono no aware.

Similarly, Sei Shonagon linked subjects that stir, excite, and delight in another masterpiece of classical literature, the Pillow Book. In that collection of poems, observations, and musings, which begins, “In spring it is the dawn . . . ,” she added her own wit to the experience of mono no aware. The “Snow on Xianglu Peak” episode from the Pillow Book, in which the author subtly demonstrates her deep knowledge of poetry, is a favorite subject for paintings.

Important Cultural Property

Court Lady Enjoying Wayside Chrysanthemums

Iwasa Matabei

Hanging scroll, ink and

light color on paper

Edo period (17th century)

Yamatane Museum of Art

Important Art Object

Nonomiya, a Scene from the Tale of Genji

Iwasa Matabei

Hanging scroll, ink and light color on paper

Edo period (17th century)

Idemitsu Museum of Arts

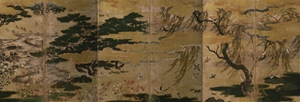

Suma and Hashihime, Scenes from the Tale of Genji Folding Screen

Six-panel screen, color on paper

Edo period (17th century)

Suntory Museum of Art

Writing Box with Nonomiya Scene in Maki-e Lacquer

Edo period (17th century)

Suntory Museum of Art

Part 4

The waka tradition and mono no aware:

The world of the immortal poets

In literary narratives, the scenes in which the sense of mono no aware is most intense are those in which poets compose and exchange verses. The act of composing a waka poem is, Motoori Norinaga has stated, inextricably connected to a profound experience of mono no aware. The waka tradition goes beyond the beauty of the words themselves to include appreciating the beauty of the kana glyphs produced by the brush and the exquisitely decorated paper on which they are written.

In the middle ages, what are known as the Thirty-six Immortal Poets, a list of distinguished poets such as Kakinomoto no Hitomaro and Ono no Komachi, became a popular theme, with portraits of the poets in a variety of styles. Each portrait depicts the context in which a poet composed his poems. We can imagine the poet’s love of the natural beauties of each season, as suggested by the Snow, Moon, and Flowers theme, and that, touched by the subtleties of human life, he was moved to create a poem.

Among paintings about poets, the Tale of Saigyo, a picture scroll linking the poems and life of the poet Saigyo (1118 - 1190), was particularly admired. Its depiction of Saigyo, traveling to places famous for their scenic beauty amidst the changing seasons and immersed in the experiences of mono no aware offered by them, creates a profound synergy between painting and literature.

Important Cultural Property

Poetry Contest on the Subject of a Newly Selected Scenic Spot in Ise

Handscroll, color on paper

Kamakura period (13th century)

Jingu Chokokan Museum

Part 5

Mono no aware and moonlight:

From new moon to waning gibbous moon

The moon gleaming in the night sky, a sight likely to invite mono no aware, has often been sung of in waka and depicted in paintings and craft objects. The Satake version of the Thirty-six Immortal Poets, a scroll dating from the Kamakura period, includes, of course, many poems about the moon.

Waves on the water,

Ripples of the shining moon,

Wrinkles of time:

Count them up and we arrive

Today at a midmost autumn.

(Translation by Edward A. Cranston)

This poem by Minamoto no Shitagau celebrates the full moon on the fifteenth of the eighth month and foreshadows, with a sense of mono no aware, the waning moon, while the moonlight illuminates the emotional responses of the mindful person. The waning moon, a subject favored by almost all schools and genres, is exemplified in this exhibition by Rimpa school poems on shikishi paper, the Willow, Bridge, and Water Wheel screens, and the lid of an inkstone case. The moon appears in the hours reserved for adults, rising after nightfall, setting near dawn. Unlike today, the moon the main source of light during the night as well as serving as clock and calendar, and it was observed and depicted it with care. An integral part of people’s lives, the moon was the recipient of a heartfelt attentiveness, far more intimate than we experience today, as these works of art tell us.

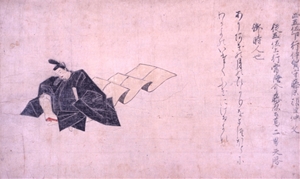

Important Cultural Property

Minamoto no Shitago: Thirty-six Immortal Poets, Satake version

Hanging scroll, color on paper

Kamakura period (13th century)

Suntory Museum of Art

Important Cultural Property

Fujiwara no Takamitsu: Thirty-six Immortal Poets, Satake version

Attributed to Fujiwara no Nobuzane

Hanging scroll, color on paper

Kamakura period (13th century)

Itsuo Art Museum

Important Cultural Property

Fujiwara no Nakafumi: Thirty-six Immortal Poets, Satake version

Attributed to Fujiwara no Nobuzane

Hanging scroll, color on paper

Kamakura period (13th century)

Kitamura Museum

Poem from the Shin Kokinshu (New Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern)

on Underpainting of Autumn Grasses and the Moon

Painting by Tawaraya Sōtatsu, calligraphy by Hon’ami Koetsu

Hanging scroll, ink on paper with underpainting in metallic pigments

Edo period; Keicho 11 (1606)

Kitamura Museum

Important Cultural Property

Writing Box with Kinuta (fabric pounding block) Design in Maki-e Lacquer

Muromachi period (15th century)

Tokyo National Museum

Part 6

Mono no aware, birds and flowers, and the wonders of nature:

The changing seasons

Themes such as Snow, Moon, and Flowers, or Birds and Flowers and the Wonders of Nature, inspired by a love of the natural beauties of the changing seasons, are derived in part from Chinese culture and poetry. They are also, however, combinations that exemplify the lyric sensitivity to mono no aware that is an unaffected part of Japanese sensibilities today. Among the many poems on the theme of the seasons in, for example, the Wakan Rōeishū (Japanese and Chinese Poems) or in the Poems Ancient and Modern, cherry blossoms in the spring and autumn foliage are frequently recurring subjects. They have also been extensively treated in paintings and in decorating craft objects, in which the glories of spring and fall seem to be competing over which is more beautiful. Similarly, the uguisu or bush warbler (Cettia diphone), which announces the coming of spring, and the hototogisu or lesser cuckoo (Cuculus poliocephalus), which announces the arrival of summer, are birds whose first cries of the year are eagerly anticipated. They have become essential elements in the many bird-and-flower folding screens that depict, from right to left, the changing seasons. Fringed pinks, hydrangeas, and the many other colorful seasonal flowers repeatedly appear on polychrome overglaze enamel ceramics and in karaori Noh costumes. This exhibition will be open from April, when spring is in full swing, through early summer. In this season of fresh new growth, listen closely, and you too may hear, off in the distance, the faint cry of the uguisu or hototogisu.

Bowl with Cherry Blossom and Maple Leaf Design in Overglaze Enamels and Pierced Openwork

Nin’ami Dohachi

Edo period (19th century)

Suntory Museum of Art

Dish with Tatsutagawa River Design in Overglaze Enamels

Nabeshima kiln, Hizen

Edo period (17th-18th centuries)

Suntory Museum of Art

Important Cultural Property

Quails and Pampas Grass Folding Screens

Pair of six-panel screens, color on gold-leafed paper

Edo period (17th century)

Nagoya City Museum

Birds and Flowers of Spring and Summer Folding Screens

Kano Eino

Pair of six-panel screens, color on paper

Edo period (17th century)

Suntory Museum of Art

Flowers and Birds of Spring and Autumn Folding Screens

Tosa Mitsuoki

Pair of six-panel screens, color and gold on paper

Edo period (17th century)

Egawa Museum of Art

Important Cultural Property

Sword guard with Kasugano Plain design

Kaneie

Cast iron with gold, silver, and copper inlay

Muromachi period (16th century)

Eisei-Bunko Museum

Part 7

Mono no aware in the autumn grasses:

A lyrical beauty of rhythm and harmony

Autumn flowering plants such as fujibakama (k) (boneset, Eupatorium fortunei), ominaeshi (golden lace, Patrinia scabiosifolia), hagi (bush clover, Lespedeza thumbergii), and susuki (silver grass, Miscanthus sinensis): if there is a distinctively Japanese aesthetic, the use of the autumn grasses as motifs is a classic expression of it. Picture scrolls, folding screens, lacquerware, ceramics, textiles: in every art form, autumn grasses are often, if unobtrusively, present. While often not the dominant motif, the autumn grasses not only establish a sense of the season but also provide visual intimations of the ambience of the scene being depicted. It is as though the expression of a moment that moved the human being in the scene is entrusted to the autumn grasses gracefully rustling in the wind―and gains a greater sense of vitality thereby.

From autumn grasses used in combination with the ashide-e technique, in which cursive glyphs are disguised in the shape of reeds (ashi) and other natural phenomena, as seen in maki-e lacquerware from the middle ages, to autumn grasses in the Kōdai-ji maki-e of the Momoyama period, with its bright harmony, to the geometrical, rhythmic expression of autumn grasses in Edo-period works such as the Musashino folding screen, the treatment of the autumn grasses motif has changed over time. The tradition of expressing mono no aware through the autumn grasses continues, however, unbroken.

National Treasure

Box with Fusenryo Design in Mother-of-pearl Inlay and Maki-e Lacquer

Kamakura period (13th century)

Suntory Museum of Art

National Treasure

Saddle with the Glyphs Comprising a Poem in Reed-hand Script, in Mother-of-pearl Inlay

Mother-of-pearl inlay on black lacquer

Kamakura period (13th century)

Eisei-Bunko Museum

Important Cultural Property

Pine Grove by the Seashore Folding Screens

Pair of six-panel screens, color on paper

Muromachi period (16th century)

Tokyo National Museum

Important Cultural Property

Chest for Books of Poetry with Autumn Grasses Design in Maki-e Lacquer

Momoyama period (16th century)

Kodai-ji Zen Temple

Important Cultural Property

Covered Bowl with Silver Grass Design in Underglaze Iron Brown and Blue, with Gold

Ogata Kenzan

Edo period (18th century)

Suntory Museum of Art

Part 8

Mono no aware in daily life:

From early modern to contemporary times

Experiencing mono no aware does not consist merely of sinking into solidary contemplation and being profoundly moved. Mono no aware is experienced and then shared. By composing poems or creating paintings or craft objects for others to appreciate, it becomes possible to share one’s emotional experience, which eases sorrow and reinforces delight. One of the motivations for elegant seasonal outings, in large groups, for cherry-blossom viewing or moon viewing parties or for admiring the autumn foliage or the snow is to share the experience of mono no aware.

Our lives are marked by many cycles: the twelve months of the year, the four seasons, morning, afternoon, evening, and night, the waxing and waning moon, the lifecycle events that compose the human life. Since we share the experience of those cycles with our forefathers, it is far from difficult to identify with the emotional experiences of those who lived in the past. The elements that evoke a sense of mono no aware are not locked away in tradition but constantly being renewed. Consider, for example, the fireworks at Ryogoku in Tokyo, which began in the Edo period and are a now a symbol of summer. When we look at genre paintings by Kaburaki Kiyokata, we sense most keenly that the heart that experiences mono no aware in episodes of contemporary life beats on today.

Within the Kameido Tenjin Shrine Precincts: One Hundred Famous Views of Edo

Utagawa Hiroshige

Edo period; Ansei 3 (1856)

Hiraki Ukiyo-e Foundation

Kitano Tsunetomi

Hanging scroll, color on silk

Showa 14 (1939)

Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2026 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31