- Calendar

- Online Ticket Sales

- Access

- JA

- EN

More and More: Unsettling Japanese Art

July 2 to August 24, 2025

*There will be an exhibition change during the course of exhibition.

*Download the list of changes in works on display

*Photography is permitted at this exhibition, except for some works.

The list of changes in worksPDF

*The order of chapters may change at the exhibition venue.

Section 1

Jam Packed!

—This and that, too!? Learn all about every design, the myriad motifs.

This section focuses on tsukushi mon, “myriad motifs” and monozukushi-e, “pictures of myriad things,” a category long familiar in Japan. Both terms are formed from the verb tsukusu, “to do completely,” “use up,” or “do one’s utmost.”

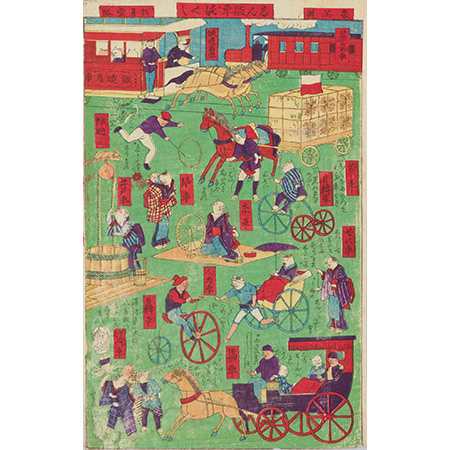

Tsukushi mon consist of a host of motifs with the same meaning or of the same type. A classic example is the Octagonal Dish with Kotobuki Character and Myriad Treasures Design in Underglaze Blue and Overglaze Enamels, with the center of the dish packed with fifteen types of treasures. How does seeing a work filled with so many hopes for good fortune make you feel? Or New Edition: Vehicles Galore, a “picture of myriad things” that brings together the many new products with “wheel” in their names, all sorts of vehicles, a popular design in the Meiji period (1868–1912)—including everything from bicycles to streetcars. Note how all the humans in this work are represented as cats. That playful expression shows us that learning about the world can be fun.

This section is also an attempt to display “myriad captions,” captions that explain everything about what, where, and how, to expand the “myriad whatever” design worldview. The captions are wordy, and jam packed, describing the works down to every detail, to satisfy your intellectual curiosity.

Nabeshima Domain Kiln, Edo period, end of the 17th century–early 18th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【To be shown over an entire period】

Ikuei, Meiji period, 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【On display between Jul. 30 and Aug. 24】

Section 2

Folding Freely

—Up to you—really!? Try folding a folding screen just the way you like it and...

You may have seen golden folding screens folded in precise zigzags at award ceremonies, wedding receptions, and other celebratory events in Japan. Those screens’ function is to add color and create a joyous atmosphere in the space.

Folding screens were originally used in everyday life as partitions, to divide up spaces. For example, the Legends of Ishiyama-dera Temple (copy), Vol. 5, shows a woman sleeping in temple, at night, with a folding screen surrounding her. The Mouse Story, Vol. 3 presents a folding screen protecting the modesty of the lady in the bath, keeping her body out of sight. Note how that these folding screens are not folded in zigzags but irregularly.

In this section, we recreate and display folding screens that are folded every which way, to suit the size of the space and the way the screens are being used. They may seem a little odd to eyes used to seeing folding screens folded in tidy zigzags. The non-standard ways of folding them may, however, bring about fresh discoveries, thanks to the way the sense of depth conveyed by the motifs is accentuated.

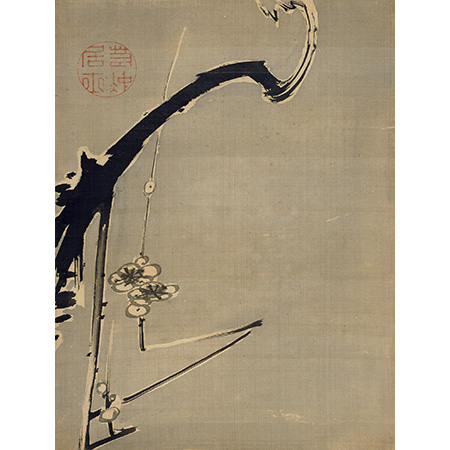

Unkoku Tōban, Left screen of a pair of eight-panel folding screens

Edo period, 17th–18th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【To be shown over an entire period (with screen change)】

Tani Bunchō, One of seven handscrolls

Edo period, 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【On display between Jul. 2 and Jul. 28】

Section 3

Lub, Dub, Love

—Unsettling in every era!? Love me, love me not—complicated patterns of love

Long ago and now, too, the heart is stirred—lub, dub. And in the works in our collection, a rich assortment loves unfolds.

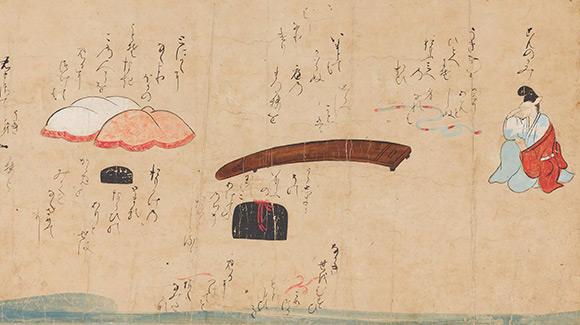

In The Mouse Story, for example, we meet a mouse that loves a human being. Gon-no-kami, the mouse who is the main character in the story, marries a human princess, thanks to the protection of the bodhisattva Kannon at Kiyomizu-dera Temple. When his true form is revealed, the princess runs away and, drowning in sorrow, he becomes a Buddhist priest. He lines up the objects from the princess’s trousseau and composes waka poems. Gon-no-kami’s state, as he quietly weeps, day and night, arouses our sorrow. Then there is Beautiful Woman, a painting by Nishikawa Sukenobu. At first glance, the subject appears to be a woman getting dressed. Note, however, her line of sight. She is looking at the portrait of Tao Yuanming, an ancient Chinese poet, painted on the partition screen behind her. If we interpret this work as actually based on a poem composed by Tao Yuanming, we sense Tao Yuanming’s burning passion for the woman.

In this section, the depictions of human relations and interpretations of scenes covertly hint at the many forms of love that are the works’ themes. Please consider intently these complex varieties of love while savoring the fascination of solving the puzzles they present.

One of five handscrolls, Muromachi–Momoyama periods, 16th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【On display between Jul. 30 and Aug. 24】

Nishikawa Sukenobu, Hanging scroll, Edo period, 18th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【On display between Jul. 2 and Jul. 28】

Section 4

Flip, Flap, Turn

—Two dimensions ⇔ three dimensions!?

Three-dimensional forms turned into interior elevations are suddenly mysterious.

Grasping the design of a three-dimensional work of art is not easy. That’s because we have to look at it from every direction and then recompose the images our eyes have seen.

In this section, what we want you to see are the truly three-dimensional designs. For example, in the Tiered Box with Hydrangea Design in Mother-of-pearl Inlay and Maki-e we see a riverside scene with hydrangeas in full bloom against the background in which an arched bridge crosses a muddy stream. This scene covers the entire body and lid of the box. If we transfer this scene to an interior elevation and compare the elevation with the work, we notice that the highest waves on the river are placed at the corners of the box, to emphasize the waves’ three-dimensional feel. In another example, the Tea Ceremony Cabinet with Rabbits Design in Maki-e, the four déformé rabbits are charming. Looking at this work as an interior elevation, we see the rabbits hopping about, as in a stop-motion animated film.

In this section, three-dimensional works, including lacquerware, ceramics, and glass, are displayed so that they can be viewed from all 360 degrees around, so that each work and its interior elevation can be compared. Comparing works and elevations not only deepens our understanding of the details of how the design and decorative techniques are connected. It also draws our attention to the creator’s clever techniques and intent.

Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【On display between Jul. 2 and Jul. 28】

Edo period, 17th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【On display between Jul. 30 and Aug. 24】

Section 5

Prick, Stab, Pierce

—Your hands can say as much as your mouth!? The stitcher’s feelings expressed in every stitch.

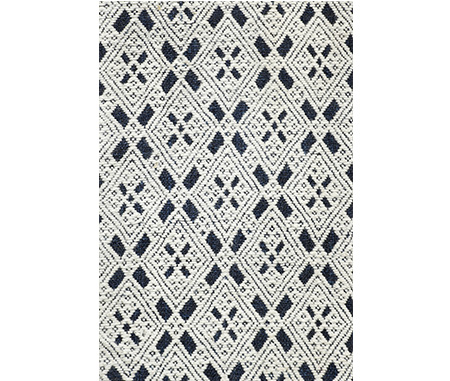

Moving one’s hands, using needle and thread, can calm and organize the self psychologically. Anyone who enjoys working in handicrafts has had that experience. This section addresses one type of handicraft, Tsugaru kogin sashi.

Tsugaru kogin sashi is a technique that women in rural villages in what is now the Tsugaru region of Aomori prefecture have cultivated since the latter half of the Edo period. For each stitch, made with cotton thread, they pick up an uneven number of warp yarns in the hemp fabric, which is woven of yarns less than 1 millimeter in width. They then follow the weft yarns to complete each stitch. Repeating that, row by row, they create beautiful geometric patterns that look as though they were woven into the textile. The basic design unit making up those patterns is called a modoko. The forty or so types of modoko are named after things in the women’s everyday lives—tekona (butterfly) or beko sashi (ox stitch), for example.

In this section, you can observe the modoko rendered in actual works and learn the modoko’s names and shapes. What is intriguing is that you can discover errors, here and there, in how the modoko are arranged or stitched. Look at the details of these little modoko and you may gain a close sense of the stitcher’s feelings, the delight—and occasional pain—of stitching.

Edo–Meiji periods, 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【On display between Jul. 2 and Jul. 28】

Edo–Meiji periods, 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【On display between Jul. 2 and Jul. 28】

Section 6

Pick up! Gather!

—Gather, organize, store!? Collectors’ love and tenacity

Just gathering things that appeal to you, arranging them, and looking at them is emotionally satisfying. That feeling is the joy that the people we call collectors have shared throughout the ages.

For example, the Seiran’en Painting Album, which contains fifteen paintings by artists from the eighteenth or nineteenth century, is said to have been tastefully selected over more than a decade. As we turn the pages in this large album, one by one, we can sense the collector’s passion and pride.

Our museum’s collection includes many groups of works that were assembled by collectors and have not been scattered. For example, the approximately 300 works of Japanese, Chinese, and European glass that the sculptor Asakura Fumio collected are, in quality and quantity, among the finest in Japan. The more than 700 Hair Ornaments and Texts that a dermatologist gathered are organized in storage chests by type and material and give us an insight into the soul of the collector as we carefully examine these works.

In this section, through anecdotes about collecting, storage boxes, and other materials, we explore the collectors’ love and tenacity. You, too, may feel an impulse to collect something yourself. We hope you will enjoy this opportunity to experience for yourself the significance of encountering these works in this place today.

Itō Jyakuchū, Edo period, 18th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【On display between Jul. 2 and Jul. 28】

Edo period, middle of the 19th century

Suntory Museum of Art 【To be shown over an entire period】

*Unauthorized reproduction or use of texts or images from this site is prohibited.

2025 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2025 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2025 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2025 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 January

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Tea Ceremony

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 February

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

2026 March

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 April

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 May

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 June

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 July

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 August

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 September

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 October

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

2026 November

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

2026 December

- Exhibition

- Closed

- Mon

- Tue

- Wed

- Thu

- Fri

- Sat

- Sun

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31